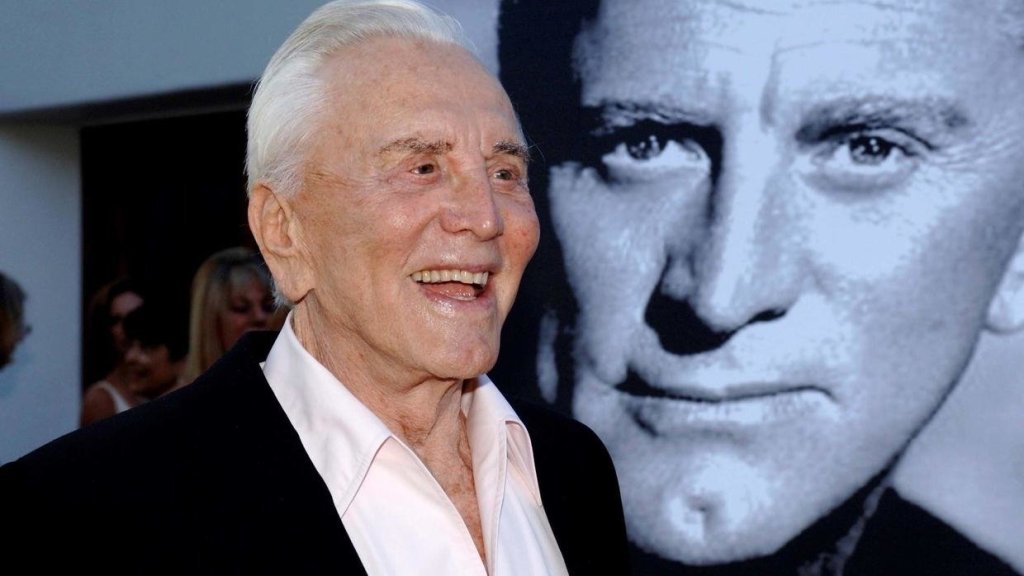

The dimple-chinned legend of silver screen that was Issur Danielovitch, aka Kirk Douglas, passed away on February 5th at the ripe old age of 103.

After serving as a communications officer in the American Navy in WWII, he undertook a prestigious stage career in New York, before being picked up by producer Stanley Kramer in 1946 for a role in The Strange Love of Martha Ivers opposite Barabra Stanwyck. From there he notched up almost 100 film credits, including some of the most iconic roles of the 50s and 60s, earning 3 Oscar nominations and an honorary lifetime acheivement award in 1996.

This list encompasses some of his best and most memorable work, as tribute to a thrillingly diverse life on screen, characterised by a great intensity and undeniable presence. Some you will have seen, some perhaps not. Considering he stopped making movies of any real significance in the 70s, his legacy is remarkably enduring. I hope you find something in there that makes you curious to revisit his work and enjoy again that distinctive snarl. He was Spartacus, but so much more besides…

Mark Robson, 1949

Already aged 32, Douglas turned down several supporting roles in “bigger” films for MGM in order to take a risk on a lead role that might get him some attention, by showcasing his physicality and skill at playing characters of ambiguous morality. His choice was vindicated, as the role of boxer Midge Kelly, a man who will stop at nothing to reach the top, earned him the first of 3 Oscar nominations and put him firmly on the map. Looking back on it now, everything about it seems dated, except Douglas, whose style, whilst still showing evidence of his theatrical roots, shone head and shoulders above the rest of the cast. Apparently a big influence on Scorsese and DeNiro for the boxing scenes in Raging Bull.

William Wyler, 1951

Adapted from a stage play that he loved, Detective story typifies the kind of roles of a man under pressure that Douglas came to be indelibly identified with. This time it was his co-star Eleanor Parker who got the Academy Award nomination, but it was their chemistry that really drew the eye. The troubles of life, and the task of being a good man in the face of a bad world were the themes Douglas tackled here. The setting of crime fighting over one day in the 21st precinct is secondary to the personal fight of the “hard-nosed” Jim McLeod, who does his best but can never get ahead. There are shadows of such films as Miller’s Crossing, LA Confidential and even Blade Runner in here. Notable for some gorgeous film-noir photography, and the obligatory Douglas breakdown speech.

Billy Wilder, 1951

It ran with the tagline “You’ll think about it… You’ll talk about it… You’ll Remember it”, and we have! Considered now as one of the most ahead of its time films ever made, thanks to the Oscar nominated writing of Billy Wilder, and his eye for how real human beings behave. A massive box office flop in 1951, it is now one of the highest rated films of Douglas’ career, still clinging on in the IMDb top 250 films of all time. As down on his luck journalist Chuck Tatum, Douglas growls his way through a performance about ambition, selfishness and media exploitation, as he attempts to rescue a man trapped in a rock fall, whilst seducing his wife and putting the life of the victim secondary to his own needs at every turn. “Not below the belt, but from the gut!” A classic in every sense.

Vincente Minnelli, 1952

By 1952, Douglas was being cast regularly in higher profile productions with higher profile acting support. But the trend of being an ambitious and manipulating anti-hero was clinging on. As unscrupulous movie producer Jonathon he was never more unlikable, and rarely more unmissable, treating Lana Turner like his personal puppet to get to the top. The film won 5 Oscars and earned Douglas his 2nd nod. Many think this was his best shot at winning, such was the degree of sophistication and animal magnetism on display. He eventually lost out to Gary Cooper for High Noon by a handful of votes, but his reputation as a bankable A-lister was cemented forever, allowing him the weight to begin a secondary career as a producer.

Richard Fleischer, 1954

In an attempt to make room for his production work, and to off-set his type-casting as hard nosed dramatic anti-heroes, Douglas took on a lighter supporting role in this adventure film, opposite James Mason as Captain Nemo. Stripy shirted Ned Land was no less macho than we had come to expect of him, but there was a degree of fun hitherto unseen in his career to date. Shot in Technicolor, with the grandeur of Cinemascope, it brought a whole new audience to his work, that may have previously avoided the gritty melodramas he was associated with. Many remember Douglas as the most exciting part of the film, as his insatiable energy dominates the mild style of Mason and eats up the screen.

Vincente Minnelli & George Cukor, 1956

In yet another attempt to widen his range, Douglas was a surprising yet perfect choice to play tortured artist Vincent Van Gogh, in his 3rd and final Oscar nominated role. He was custom made to portray the wild passion and intensity of the artist, but it was his quiet moments of calm genius that really impressed. This time he lost the award to Yul Brynner for The King and I, as big, colourful productions began to dominate; also watching on as co-star Anthony Quinn picked up best supporting actor. There are rumours Douglas was less than happy to lose out, and he made a personal vow to soon enter the arena in a big epic that would sweep the board… Although many believe his artistic star had peaked here with the more subtle Lust For Life.

Stanley Kubrick, 1957

Meanwhile, producer Kirk Douglas had met a promising young director he liked called Stanley Kubrick. Douglas, whose humanitarian work was also becoming a big part of his life around this time, was looking for a script that championed pacifism over the gung-ho attitude of American heroism that he found distasteful. The rest is history. Possibly the one film in his career that can still be called perfect. Again, it was way ahead of its time, and therefore unfairly shunned as an Oscar contender. Shot in stunning black and white, it is an economical film of great power, replete with memorable moments and striking dialogue. The evidence of Douglas’ increasing skill at the quiet moments is all the better for the big pay-off when he erupts, calling out his superiors on their morality and cowardice. Of all films on this list, this is the one most likely to endure as a work of pure art.

John Sturges, 1957

In another piece of perfect casting, Douglas realised that in this old tale of massive mythological appeal the role of Doc Holliday is far more interesting than the lead of Wyatt Earp. Even so, he managed to earn level billing with lifelong friend Burt Lancaster, such was his box office draw at this point. The two had worked together before, but it wasn’t until this hugely entertaining western that they really bonded; apparently laughing so much between takes that on several occasions director John Sturges sent them home, as no work was possible that day. Douglas also talks in his auto-biography about how he became obsessed with how many times Doc would cough in a scene to maintain continuity – evidence of just how seriously he did take his screen work and craft.

Richard Fleischer, 1958

In a productive period seeing him make four or five films a year, Douglas returned to work for Richard Fleischer in his pursuit for the great epic that would finally win him the Oscar. The Vikings was a star-studded spectacle that despite some memorable scenes between himself and Tony Curtis, falls a little flat as a satisfying film in entirety. A box office hit, but a critical flop, it has to be counted as somewhat of a failure, except for the fact it is one of the better known moments in his career, thanks largely to the powerful visual of Douglas with a dead eye and scar; proving you merely point a camera at him and get magic. My favourite trivia around this film is that Douglas offered a prize for best beard on the first day of shooting, only to turn up himself entirely clean shaven.

Stanley Kubrick, 1960

And here it was! The film that Douglas as star and producer had been working towards for his whole life. At the age of 43 he threw his entire being into making this the difining moment of his career. Although we do remember it with extreme fondness, it was a troubled production by any stretch. Original director Anthony Mann was fired by Douglas months into filming and replaced by Kubrick, who Douglas admired unreservedly after Paths of Glory. The trouble was that Kubrick himself was out-growing Douglas creatively and the two also clashed, to an almost catastrophic degree. Film legend will tell it different ways, but such was Douglas’ ego by this point that he virtually directed it himself; a fact Kubrick would never again endure, to the point of almost disowning the final product. So many iconic moments and a re-watchability factor belie what a painful experience it was for all its stars. Douglas had to watch on again as this time Peter Ustinov won the supporting actor gong, whilst Douglas was not even nominated. A great irony that his life’s work culminated in a film that to some extent broke his heart.

David Miller, 1962

Two years on and Douglas has returned to the safety of westerns, looking older and gaunt, if no less charismatic. Something had cooled in him since Spartacus, and approaching 50 years of age, you can see the maturity and heart-ache most evidently in this performance. The tough guy remains, but there is a wistful aspect to Jack Burns that was not there before. He utilised the writing talents of one Douglas Trumbo to convey a “sadistic harshness” he called “the most perfect script I ever read”. Reportedly, in later years, Douglas considered this his best work, and son Michael (who you may have heard of) has also said this was his favourite amongst his father’s prestigious oeuvre. In that context alone, it is worth watching again.

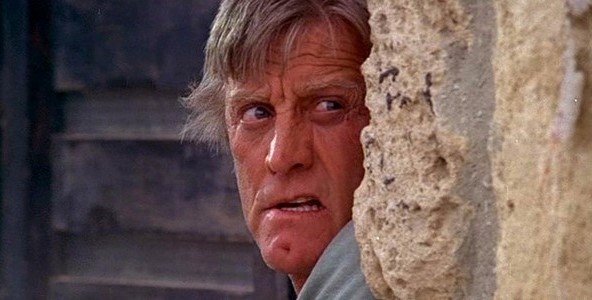

Brian De Palma, 1978

In the last of this list we skip forward 16 years and some 25 film credits. Not that there wasn’t any work of quality in that period, but because the edge that existed in the younger man had undoubtedly waned, with Douglas often miscast or out of his depth. Aged 62 he stumbles upon a role in a psychological horror movie that is quintessentially 70s. The reason I believe this is the last movie of real note he made is that it was a committed performance that returned him to the idea of being an angry underdog. Essentially a thriller, Douglas revels in the fear and anguish of a father pushed to the edge of his abilities to save his son. Even though he would go on to make many more films, you feel the last of his real fire was given to this role. It also proves to me that despite a lifetime of activity the real grist of his career lasted only 16 years: 1946 – 1962. The rest was a man who knew cinema better than anyone, but couldn’t always outrun his own type-casting.

In conclusion, the history of cinema owes a great debt to Kirk Douglas. He was known privately as a kind and giving man, with a terrific sense of humour; a loving father and a great benefactor to many worthy causes. Few legends of the golden age still remain, and it is worth remembering to watch and rewatch the classics he was a part of, in the context of film arts and what it means to create lasting images and stories. RIP.

I hope you enjoyed this list from The Wasteland. The forum is open for your comments, as ever. See you again soon for another 12 of the Best…