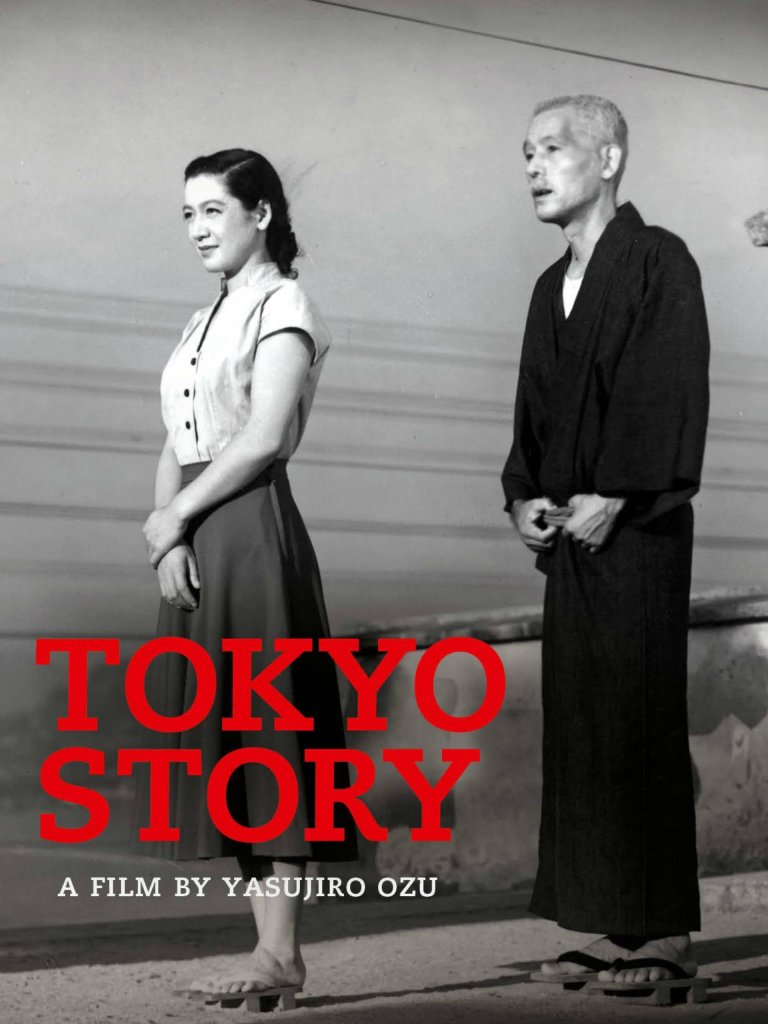

As part of the period during Covid when watching movies could involve a little more discernment and patience, I decided to finally engage with Ozu’s apparent masterpiece and oft cited “best film ever made”, Tokyo Story. Intimidatingly, it is rated as the #209th best film of all time on iMDb, with a 100% rating on Metacritic from 18 critics – an almost unheard of feat of unanimous praise. Having seen Late Spring earlier in the year and finding it exquisite but ponderously slow, I approached this experience with some doubt as to whether I would enjoy it as much as the serious cinephile world wants me to.

Indeed, I sat through it in absolute admiration of every shot and scene, masterfully crafted with obvious care and pervasive wisdom. But I felt detached and cold, my western eye craving some more direct drama or action. But Ozu deliberately avoids those things in favour of deeper emotions, suppressed to the point of invisibility. What is best about it is what is not there. And, in that way, it is an astonishing magic trick that I suspect would reward multiple viewings with infinite nuances and detail. However, will I ever find the patience and calm within myself to go through it again? I am in doubt.

For me, watchability is a huge part of a film’s quality, and therefore, whilst it clearly stands as a monumental work of cinematic art, it does lose big points in the Decinemal ratings system of my own design. Yet, comparing it to anything more exciting, with fast-paced entertainment, is like trying to compare a cherry blossom to a Ferrari. To appreciate Ozu you have to let go of all Western ideas of cinema as “fun” – this experience is as bitter and cleansing as drinking a Japanese flowering tea. You won’t enjoy it, as such, but you will feel a better person for having done it.

Things that are striking in particular are the long lingering shots from a low level. These are called “tatami” shots, named for the bamboo floor mats typical in Japanese homes. The idea of the camera being so low is to give an impression of humidity and grace that respects the subjects being filmed without prejudice. There are no fast edits, and very rarely a pan or slow zoom. Instead, we are allowed to focus on the faces and body language as they appear in nature and in the context of each human relationship. There are few distractions externally. The sounds are voices and the breeze. The images are homes and clothes and melancholy faces, longing for something close but always far away – something just out of reach. Also, there is the style of performance, which is utterly unique and fascinating.

At no point is anything over-stated, in favour of holding on to emotion for as long as possible. The inner tension is palpable, expressed delicately and with a naturalism that seems utterly typical of what it means to be Japanese, whilst still maintaining a universal feel that allows anyone to recognise the human aspects at stake. Loneliness, boredom, regret, hope, familial obligation, romantic love vs. responsibility – these are just some of the themes on display if you want to find them.

Essentially, I can’t claim, yet, to be a massive fan of Ozu. His work is too tepid for my Western palate. Going back to the tea analogy, I know green teas are good for me and will make me feel good, but I just prefer something more exciting, so I rarely drink one. I have to be honest and say that is how I feel. Maybe in another 20 years I will mature into them, but for now they are a curiosity in my film education and not much more. I do recommend you also try for yourself, there is a lot to admire for sure. Just don’t expect to be blown away to the extent of claiming it as your new favourite film.

Decinemal Rating: 74